Please Welcome Award-winning Author Micki Browning!

Author Interview

- What does it mean to plot from the POV of the antagonist and write from the perspective of the protagonist?

- What’s your experience and how did it help with writing?

The best writing advice I ever received was to plot from the point of view of the antagonist and write from the perspective of the protagonist. Simple, right? But it was an a-ha moment for me.

A bit of background. Like most writers, I have a couple of practice manuscripts currently occupying space in the bottom of a drawer. They both garnered decent feedback from agents, but the novels were episodic—most of the second act chapters could have been rearranged without affecting the story. I wasn’t building on prior events. Why? Because I didn’t know what my antagonist was doing behind the scenes.

I think most writers put a great deal of thought into the character development of their heroes, but they tend to give their antagonist short shrift. But think about it—the antagonist is the character that drives the story. It is his or her actions that the protagonist must address.

For most of my adult life, I was a police officer. Part of the job description involved investigating crimes. Most incidents began when someone called 9-1- 1. Upon arrival, I’d try to piece together what happened by observing the scene, obtaining witness statements, and collecting physical evidence. Armed with this information, I’d search databases, develop additional contacts, run down new leads.

I was a first responder—just like my protagonist.

Imagine how easy police work would be if an officer knew before being dispatched to the scene exactly how the criminal had planned the crime, what motivated the person to do such a nefarious deed, and what steps he’d taken to avoid detection.

As a writer, you can do that!

To combat my story-structure issues, I enrolled in a plotting course for mystery and thriller writers. During the course, the instructor assigned two exercises that I’ve since incorporated into the planning stage of every story I write.

The first exercise explains the antagonist’s motivation for doing what he did. I write it in first person and it essentially creates the backstory of the character. The first line of this exercise for Adrift, my debut novel reads:

Ishmael Styx is a man who knows what he wants, and he wants to be dead. All he has to do is figure out how to make it temporary.

I then wrote 1200 words explaining what had happened in his life to bring him to this

point.

The second exercise explains how the antagonist pulled off his crime. Adrift had a complicated crime (more than one, actually, but that developed later in the story).

Drawing on my background, I hatched the plan. Knowing how the crime occurred gave me the insight I needed to identify the clues my protagonist had to notice, what other things could be misinterpreted, and how to follow the breadcrumb trail left by the antagonist. The exercise revealed some surprising options that prompted me to go deeper into my storytelling.

The structure of a mystery novel is such that the antagonist runs the show in the first act. His crime is the inciting incident that ensures the protagonist’s involvement. Roughly the first half of the story involves the hero reacting to the actions of the protagonist. After the midpoint, their roles change. Now your protagonist is hot on the trail, developing those leads, realizing her mistakes. Sure, she’ll have setbacks, but as she gets closer to solving the crime, the two characters are also nearing their final confrontation. Both exercises will help you determine how your cornered antagonist will lash out, try to escape, or outwit your sleuth.

Mapping out the crime allowed me to structure my storyline so that it built on the information learned in previous chapters. Actions had consequences. My writing was no longer episodic.

The first time I’d put this writing advice into action was during the writing of Adrift. The novel won both the Daphne du Maurier Award for Excellence and the Royal Palm Literary Award for mystery. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

I knew how to foil the crime because I had plotted it first.

BIO:

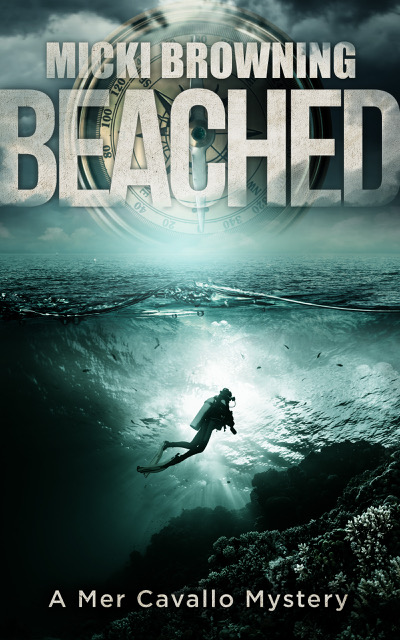

An FBI National Academy graduate, Micki Browning worked in municipal law enforcement for more than two decades, retiring as a division commander. Now a full time writer, she won the 2015 Daphne du Maurier Award for Excellence and the Royal Palm Literary Award for her debut mystery, ADRIFT.

Micki also writes short stories and non-fiction. Her work has appeared in dive magazines, anthologies, mystery magazines and textbooks. She resides in Southern Florida with her partner in crime and a vast array of scuba equipment she uses for “research”